Origins, vegetation succession and carbon dynamics of northern peatlands

Background

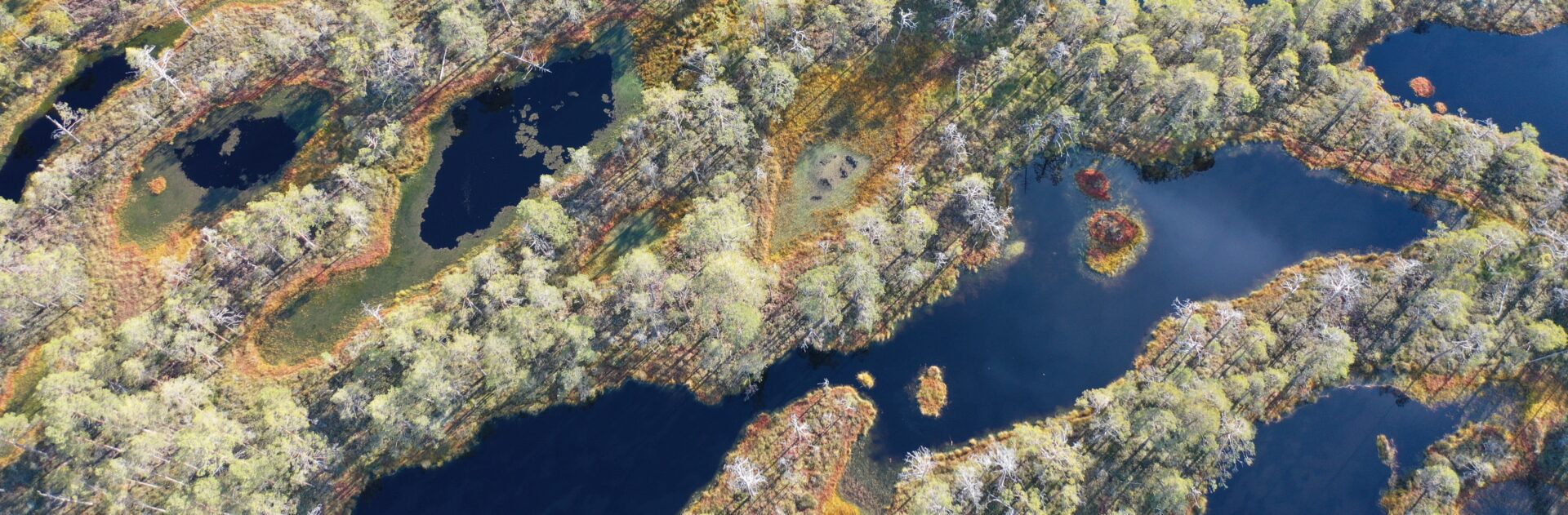

Peatlands are terrestrial wetlands where persistent waterlogging inhibits plant decomposition, leading to the accumulation of carbon-rich peat. Since the Last Glacial Maximum (~21,000 years ago), peatlands have gradually expanded across deglaciated regions of the northern hemisphere. Today, they store up to one-third of global soil carbon – comparable to the carbon content of the atmosphere – making them vital components of the Earth’s carbon cycle. Peatlands are also highly sensitive to climate change, land use, and wildfire. Despite their importance, the processes that govern peatland initiation, ecological succession, and long-term carbon sequestration remain poorly understood. This project aims to address these knowledge gaps by investigating environmental controls on peatland development and carbon dynamics across large spatial and temporal scales.

Project Overview

The project will address three interlinked questions about the long-term development of northern peatlands. Each will form the basis of a thesis chapter and a peer-reviewed publication. Research will be primarily desk-based, using simulation models and meta-analysis tools developed by the supervision team, with opportunities for UK and overseas fieldwork depending on your interests.

- What controls peatland initiation? Previous work by the supervision team (Morris et al., 2018, PNAS) showed that warming growing seasons after glacial retreat enabled peat-forming vegetation to colonise waterlogged postglacial landscapes. However, the timing and mechanisms of peatland initiation vary regionally, suggesting that factors beyond climate – such as topography, hydrology, and substrate – also play key roles (Gorham et al., 2007, QSR). This part of the project will analyse basal peat and sediment layers to identify initiation pathways, including terrestrialisation of lakes, paludification of forests and tundra, and peat formation directly on bedrock. A meta-analysis of published palaeoecological records will be combined with climate simulations and geospatial analysis to understand how landscape characteristics influence peatland formation. These insights will also inform predictions about the future of currently deglaciating regions, such as the Antarctic Peninsula, where moss banks are forming nascent peatlands.

- What drives plant community succession in peatlands? Peatlands often begin as fens: nutrient-rich, high-pH ecosystems fed by groundwater and runoff. As peat accumulates, the surface rises above surrounding hydrological inputs, and precipitation becomes the sole water source. This transition to a bog is marked by declining pH, nutrient levels, and biodiversity, along with changes in carbon gas fluxes. While climate has been proposed as the main driver of fen-to-bog transitions (e.g., Väliranta et al., 2017, The Holocene), preliminary findings by the supervision team suggest that topographic position and peatland age may be more influential. This component will focus on Finland, where strong spatial gradients in fen and bog distribution will help interpret meta-analyses of peat core data showing past transitions. Combining modern geospatial data with palaeoenvironmental records will support projections of future changes in fen and bog distribution under a changing climate.

- Simulating controls on long-term carbon sequestration. There is ongoing debate about how to interpret carbon accumulation rates from peat cores. Apparent rates – derived from age-depth models – may not reliably reflect past accumulation due to decomposition removing and over-printing information after peat formation (Young et al., 2021, Scientific Reports). This part of the project will use the DigiBog model, developed by the supervision team, to simulate peat accumulation across climatic and latitudinal gradients. These simulations will help interpret apparent accumulation rates from well-dated cores, improving understanding of long-term carbon dynamics in peatlands.